Civil Bombing Decoy SF1 (c)- Downside

The

WRINGTON WARREN

StarFish

by

Ross Floyd

with additional material by Frank Newbery, Ruth Coleman and Dave Ridley.

Illustrations – Gill Floyd.

Advice, editing, encouragement – Bill Woolstencroft.

Contains public sector information, photographs & illustrations licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/c. Ross Floyd 2020

D

uring World War 2, of all the cities in Britain, Bristol was the 6th most heavily bombed by the German Luftwaffe.Between the end of November 1940 and mid April 1941 there were six major ‘Blitz’ raids directed at the city. While this was nothing like the scale experienced by London and some other cities, Bristol suffered 548 air raid alerts and 77 raids that released over 1000 tons of high explosive bombs and a quarter of a million small incendiary devices. 1300 people were killed, a further 3000 seriously hurt and 80,000 buildings damaged of which 3000 were destroyed or required demolition. With totally ineffective ground defences and no worthwhile night fighter force until the spring of 1941, the only realistic defence was deception.

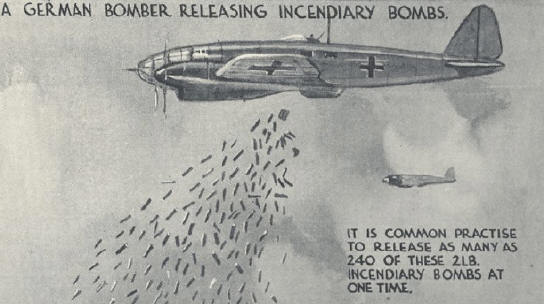

The firebomb did far more damage than high explosive types due to the sheer numbers dropped over British cities.

Any one small inexpensive bomb could start a fire and destroy an entire building – or street , and they fell in thousands.

Walking along the public footpath over Wrington Warren adjacent to Brockley Combe in North Somerset you soon find yourself deep in English woodland, a tranquil setting only disturbed by the roar of aircraft passing overhead as they leave Bristol Airport less than a mile to the South East. Looking away from the sky as the noise fades, amongst the trees you may notice long trenches and many circular holes in the ground some up to 30 feet in diameter with low banks around them, generally spaced in short rows or pairs, with each group generally similar in size, number and depth. There are also a few much larger ones looking like shell craters from the Western Front.

While clearly many years old and with mature trees growing in some, it is generally believed that all the depressions were old stone workings, yet the rows seemed to point towards Bristol and deeper in the woodland are tracks surfaced with brick and rubble from roughly cast low grade wartime concrete clearly broken apart and part buried in the ground with various wires and pieces of metal still attached. Incredible as it may seem today, in the Winter of 1940 and early 1941, this now peaceful woodland was a scene of almost Biblical fire and fury. You are standing in the target zone of what was once Civil Bombing Decoy SF1 (c) the Downside StarFish. The rubble underfoot comes from parts of Bristol that could not be saved from the rain of Nazi bombs and was transported to the area as road making material during post war reconstruction..

By the end of the Second World War 237 decoy sites had been constructed in Great Britain and N Ireland and it is estimated that over 2500 civilian lives and countless buildings, equipment and facilities had been saved from destruction by a completely passive defence, decoying and the creation of visual misinformation.

Although there were many other military and civilian decoys in the area, this article will look particularly at the larger decoy fire sites and in especially Decoy SF1 ( c ) at Downside and its subsequent relocation to Brockley Woods, near Bristol.

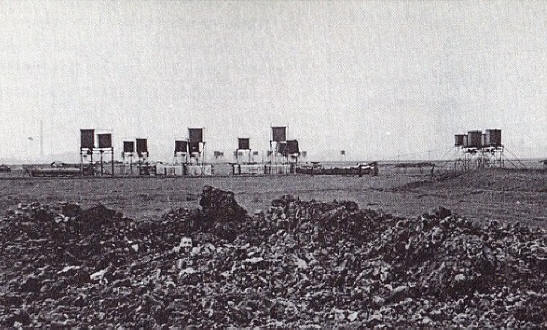

A StarFish ‘somewhere in England’

A

fter the German attacks on civilian targets in Warsaw, Rotterdam and earlier in the Spanish Civil War it was abundantly clear that all targets civilian and military would be regarded as legitimate for high explosive and fire bombs and British military planners had begun to consider how this could be countered long before the inevitable war with Germany actually started. Anti aircraft defences were little changed from the 1914-18 conflict and it was clear that something had to be done urgently. Although at first there was no intentional bombing of German or British civilians( as opposed to others ), this situation didn’t last and after the Nazis dumped high explosives on the residential East End of London in a botched raid on industrial targets in the docklands, leading to British retaliation on Berlin, the situation quickly spiralled out of control.While France was unoccupied, it was impossible for the technology of the time to assist long range night time navigation, but once Germany occupied the entire European coast, Luftwaffe engineers were able to set up widely spaced radio transmitting stations that gave intersecting transmissions and thus pinpoint accuracy to their newly developed radio navigation systems. In a matter of weeks German aircraft were no longer blundering about over hostile territory in the dark as the RAF were over Germany, but instead could rely on electronics to locate and bomb a target with an accuracy of a few yards. The threat from accurate German day bombing had been seen off by the RAF during the Battle of Britain, but was now just as accurate in darkness and poor weather, and there was nothing the British defences could do to interfere. This was the stuff of nightmares for the British authorities.

The idea of creating decoys to confuse bombing was first mooted in May 1938 by Group Captain F J Linnell, Deputy Director of War Operations at the Air Ministry and after the usual British discussion and bureaucratic dithering, a recently retired Royal Engineers Colonel, John Turner was appointed to oversee the creation of bombing decoys. Turner had huge charm, drive, tenacity, iron determination and a way of persuading people with no intention of cooperating to willingly do his bidding. He was also a qualified pilot and had been involved in military airfield construction in the Middle East. Nicknamed ‘Conky Bill’, which he used himself, he was put in charge of the national decoy system in late 1939 and when bombing began in earnest he was given carte blanch to draw on any resources necessary to create a working decoy system.

Col. Sir John Turner

The project was beyond top secret, so secret it didn’t even have an official name, and was simply known as ‘Colonel Turner’s Department’. Turner was given a level of authority unheard of for any Government Official, to requisition anything and to act as he thought necessary, reporting directly to Churchill and the War Cabinet. To his ultimate credit this was used wisely and sparingly but unsurprisingly the lack of official identity didn’t help at all when a War Office official turned up to requisition land, equipment and manpower from an unsuspecting RAF base or private landowner.

The ultimate aim was to simulate towns, factories, military installations, airfields, docks and transport facilities and to lure bombers from centres of population, economic and military sites and to create confusion and discord amongst the enemy. Decoy construction began as the Battle of Britain was reaching its height, and the Blitz on London just beginning but like all official projects, nothing substantial happened for some time. StarFish was a typically eccentric British idea but like radar in the Battle of Britain it was only part of a much larger operation involving science, intelligence, deception and in this case considerable amounts of visual illusion.

Aside from finding suitable sites for decoys, near enough to the target to be believable but far enough away not to risk civilian lives, decoys had to be constructed and meet various operating requirements, and then reliably maintained. For this Turner used the skills and ingenuity of the special effects department at Norman Loudon’s Sound City Film Studios at Shepperton. Loudon was the world expert at film props and effects and was pleased to be able to assist the war effort by turning his team of designers and set builders from theatrics to something rather more serious. Turner handled the policy, driving the project relentlessly and with charm, fending off officialdom that as always opposed anything new. Loudon and his special effects team built everything from special fire baskets, detailed dummy lighting systems to represent airfields and factories and even as the war progressed, inflatable dummy aircraft and complete hoax airfields that were good enough to attract real aircraft in broad daylight..

However that was all to come and the first decoy fire was rather less well planned. Despite the obvious danger building in Germany and Turner’s efforts, ‘The Establishment’ took 18 months of discussion before the first decoy site was even commissioned, yet when it finally happened the whole process took under 12 hours from inception to ignition. Despite all the discussion nothing substantive had happened but on a November morning in 1940 intelligence sources warned of a huge bombing raid planned that night, aimed at the industrial Midlands. The target was not known but the intersecting radio beams used for German navigation gave clues. The authorities panicked and looked for any way to build a decoy, possibly as much to save face as lives. A group of junior RAF officers patiently waiting for a transfer bus were rounded up and seconded into bonfire building. In a few frantic hours, a small number of oil and mud drenched air crew managed to build the first working bombing decoy to divert a major air raid on the Midlands. The Germans then failed to arrive as anticipated and instead bombed Coventry, tearing the heart out of the city with 500 tons of explosives, 50 parachute mines and 36,000 incendiary bombs. Huge damage was done - there were 560 deaths and over 1200 injuries.

Turner’s concerns were valid and suddenly decoys became the number one priority for those who should have known better long before.

I

n the dark days of 1940 & 41, there was no effective method of defence against the nazi bombing campaign that was decreed by Hitler to do as much damage as possible to economic and civilian targets. After the Coventry raid, the building of bombing decoy sites began in earnest around major cities in the UK. At a time when Britain had very few effective night time defences it was necessary to use any means possible to divert German bombers. Decoy sites were a cost effective and relatively quick way to provide at least some protection on a country wide scale, using locally available materials and very limited manpower.

A German ‘Herman’ 1000 kg blast demolition bomb . Most bombs used were smaller 250 and 500 kg high explosive types. The name came from the Herman Goring the Luftwaffe Chief who was also very heavy!

Target finding and marking were in the hands of a few expert German pathfinders who could navigate using the new electronic beam systems, locate the aiming point and then drop parachute flares to illuminate the ground and release incendiary bombs to start fires that would act as target markers for the less experienced main force coming along behind. Good visibility and timing were essential for both sides. Everything depended on the pathfinders. In good weather and on a moonlit night navigation and bomb aiming was easy, especially if the target was on an obvious geographic point like a river or coastline, but if the weather was poor as usually the case in Britain during Winter, if there was no moon or the electronic navigation could be disrupted, then there was a good chance that the main force would miss the flares and initial fires and be enticed to drop their bombs on open fields, wasting their efforts and saving death and destruction below.

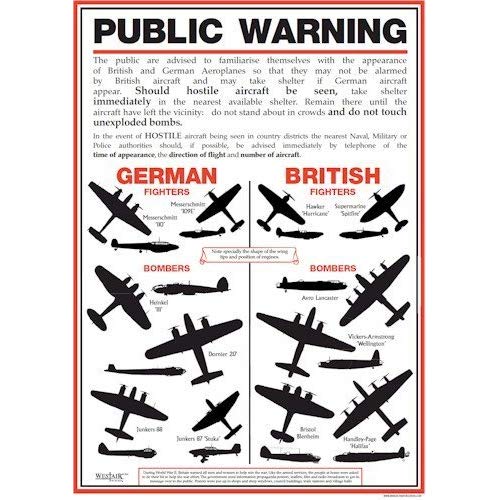

From a plane at night it is very difficult to judge relative size and for decoys to be effective, spectacular results were more important than size on the ground. Navigation despite upcoming electronic aids was basic, much depending on dead reckoning, star sights and map reading by moonlight. If the civil lighting blackout below was good and all windows and lights masked, which was virtually impossible in a small village let alone a city, the aircraft navigator would have nothing to pinpoint his position and without radar or electronic navigation could be easily confused. Some German planes, in particular the HE111 were designed as day bombers and had huge areas of clear Perspex in the cockpit, making external visibility in darkness almost impossible due to reflection and refraction. Even landing at night was risky and many planes came to grief as crews were not experienced in night flying. Thus although the Germans had electronic equipment , they lacked the means to deliver it unless visibility was good.

That was where the Decoys, if well organised and controlled, could perhaps succeed.

A German 1800 kg ‘Satan’ bomb. The largest bomb in general use.

S

tarFish decoys, or Q sites, the name coming from the term Special Fires or SF and hence the code StarFish, protected larger towns and cities as well as industrial sites and were used in conjunction with radio countermeasures that interfered with German directional radio beams used for navigation and later semi automatic bomb aiming. The decoys were intended to replicate a specific target and this was fundamental to the design and layout so that it appeared genuine from the air. Every decoy was different and the actual equipment installed depended on the site and ‘target’. The decoys had to be at least half a mile from the nearest habitation and the ground needed to be suitable. However size was not as important as appearance as the German aircrew would only see what they were intended to and it was very unlikely that a whole target would be on fire at one time, thus a few well positioned special effects could simulate a huge area under attack.Decoys were the end of a long line of counter measures and part of a hugely complex piece of integrated intelligence and scientific work that discovered the Germans were using a long range Lorenz type radio beam transmitted from France with intersecting radio cross beams to mark aiming and release points for bombs. A bomber had to fly along the beam which was directed over the target in Britain from radio stations in France and Germany. The main beam was made up of two components which would indicate if the aircraft was to the left or right of the centre line by changing from a steady note in the pilot’s headphones to dots or dashes if the aircraft deviated. When the first intersecting beam was crossed a different sound warned of the approaching target, and the second beam signalled it was the moment of bomb release. It was simple and accurate, but had a massive flaw. By detecting the radio frequency and then jamming the signals, altering the characteristics of the radio signals or adding a spurious cross beam signal, the ‘target’ could appear to be at a different point on the main beam or off to one side – and the entire system could occasionally be thrown into such chaos that the navigator and pilot of the bomber lost all confidence in its ability to direct them anywhere! This became known as ‘Bending the Beams’ which was not technically correct but gave a good idea of the result. By throwing the aircraft navigators off track electronically, enforcing a total blackout in the real target area and then providing an alternative ‘target’ that appeared to have been bombed already, it was hoped that the real location would escape at least some of the attack.

Larger sites were constructed to represent a whole city with combined lighting and fire effects that covered many acres of open land as at Blackdown on the Mendips south of Bristol and Sinah Common near Portsmouth. Smaller sites and individual illumination systems could represent a single factory or feature that might draw bombs or of equal importance, be mistaken for a genuine navigational landmark and thus add to the overall deception and inaccuracy of the bombing and navigation which could be just as effective at destroying aircraft as gunfire.

Other decoy specialities were ‘inland’ harbours – complete with dock lighting and pools of water to give a realistic reflection, fake railway sidings where red lights in a box would be faded on and off or intermittently displayed by mechanically opening and closing flaps to simulate railway engines with opening fire doors. Red and green ‘railway signals’ were also built. Flickering lights appeared to be factories with furnaces or heat treatment processes, sheds were fitted with lights and the doors opened and closed automatically to break the ‘blackout’ and skylights were placed in fields with lights under them to simulate a faulty blackout in a factory, all intended to draw bombs from the real targets. There were even simulated airfields with a flare path, car headlamps simulating taxiing planes and a trolley that careered along wires just above the ground showing navigation and landing lights looking like a landing aircraft and inviting attack. For daytime effect, false runways, dummy buildings and inflatable or canvas dummy aircraft were built, masterminded by the special effects team from Shepperton.

A decoy site set out to mimic a particular aspect of night time activity appropriate to a specific target. Arranged to imitate the correct distance between the various identifying points of the genuine target and providing a visual marker intended to confuse aircraft navigators into thinking that the ‘town’ or industrial complex had then been plunged into darkness as the blackout was enforced with the arriving raiders. A fire decoy would portray burning and collapsing buildings, individually or in lines, giving an impression of city streets, a true vision of Hell from 15,000 feet. Depending on the type of decoy, an apparently random mass of earth tumps, cables, lights, tanks on scaffolding stilts, concrete troughs and unsurfaced tracks by day, became a very realistic replica of the local city by night with dim lights, factory furnaces and railway traffic all with a very indifferent blackout that would have had any genuine ARP Wardens yelling ‘Put that light out’ with unreserved venom.

Barrage balloons deterred low level raiders and endangered our own aircraft, but not the high altitude night bombers and one of the main drawbacks of a night decoy was enthusiastic if completely ineffective anti aircraft defence from the nearby genuine target. Although ‘AA’ guns were plentiful around most important sites, they had no way of accurately targeting aircraft in the dark and fired blindly, trying to fill sections of the sky with a steel box barrage and sometimes rocket propelled steel cables, in the vague hope of hitting something – they didn’t. Despite being useless, the big guns did wonders for civilian morale with thundering explosions and huge flashes until the remains of the shells fell to earth breaking tiles and occasionally hitting people. What goes up must come down and there was often a lethal rain of steel splinters quite independent of the German’s antisocial behaviour, falling cables and shrapnel creating absolute havoc with power lines, road and rail transport. A few decoy sites had guns and in the case of the Mendips and Donwnside, anti aircraft rocket batteries. Bombing a relatively undefended burning target when all around was blackness was logical, but if a few miles away heavy guns and searchlights were in full operation, illuminating the darkness with blinding beams of light and splitting the night sky with huge if ineffective explosions, the game was rather given away and once major fires took hold in the genuine target area, the decoys were of minimal use.

Once the raiding aircraft were well in sight of a main decoy with clearly illuminated houses and factories, the spoof ‘blackout’ would be ‘enforced’ and the dummy ‘city lights’ extinguished, with a few ‘accidental’ and apparently random lights pointed skyward to attract attention. Hopefully confused by electronic countermeasures the leading aircraft would now attack the decoys. At the StarFish site nearest the raiders approach, fuel would be turned on and the fire baskets ignited electrically by the crew stationed 1000 yards away in a ‘bombproof‘ bunker – usually an earth hump with brick walls and a 9” concrete roof. The fire effects would then be fed automatically from the on-site oil tanks with Coventry Climax petrol engine generators in the bunker providing power for any decoy lighting and the ignition systems. It would appear from the air as if the leading bombers had started major fires in the target area.

In addition to confusing the leading pathfinder aircraft, decoys also took advantage of the less experienced main force aircrew without electronic navigation aids who followed behind the leaders and were briefed to drop their bombs on the ‘chandalier’ marker flares and fires left by the leading bombers. It was all about those first few minutes between the departure of the pathfinders and the arrival of the inexperienced main force bombers.

In the case of a Minor StarFish, as the main force of bombers approached after the pathfinders had gone over, rapid ignition of the decoy fires would give the appearance of a blazing ruin under the flight path just a few minutes flying time before they expected to see it. Navigation was not that accurate in the early years and hopefully they would assume that their path finding colleagues had already started to fire bomb the target city and created a nice blaze onto which they could dump their phosphorous, oil bombs, incendiary and high explosive munitions. Rapid fire fighting in the real target area was also vital, not only to reduce damage but to allow the decoy fires to appear as the larger ones and thus the real target.

The StarFish would rapidly become a major conflagration, hopefully assisted by munitions imported from Germany, before settling down to a steady two or three hour burn with occasional spectacular explosions and ‘collapsing buildings’. Some fire baskets were arranged to appear from the air like flames coming from the windows of buildings and others generated huge volumes of smoke, all intended to deceive navigators and bomb aimers. Most decoy sites were arranged so that they were between commonly used navigational markers and the protected city ( in the case of Bristol , Steep Holm, Brean Down and Avonmouth ) so that the planes had to over fly the decoy before reaching the real target and hopefully drop their bombs too early, hoping to get away from the anti aircraft guns and barrage balloons. Thus there were electronic, visual, navigational and psychological aspects of the operation.

On cloudy nights and when the radio counter measures were successful it had some effect, but on a clear night when aircraft could follow the coastline and rivers, it was completely useless and in many cases the sites remained unlit as the planes went overhead and the controllers did not want to give away their position as a decoy. Success was dependent on cloud cover, visibility and timing and on some nights there was no result, but on others, Downside, Lavernock near Cardiff and Sinah Common outside Portsmouth being particular examples, a major part of a bombing raid was completely or partly diverted when everything went according to plan for the defenders. When it didn’t, the result was what happened at Coventry in November 1940 when the City Centre was destroyed – or ‘Coventrated’ as the Germans so delightfully put, it or at Bristol when the Easter raid of 16th March 1941 wrecked the city centre after a promising start by the decoy system.

The idea was copied by the Germans later in the war and had some success when British radio navigation was jammed but it took a special kind of courage for the operators of a decoy to turn themselves into a live target. This was especially so when the sites were struck by bombs and needed to be refuelled or reignited manually, or repairs made while a raid was in progress. Those on the ground were actually inviting a rain of high explosives onto their heads.

Defence against the Firebomb

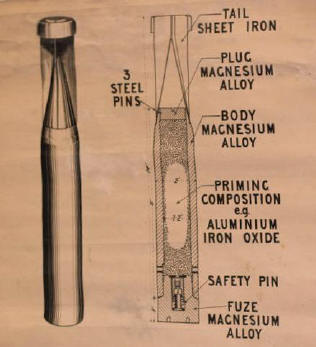

A wartime diagram of an incendiary bomb – dropped in thousands they did far more damage than more spectacular munitions as they started hundreds of fires.

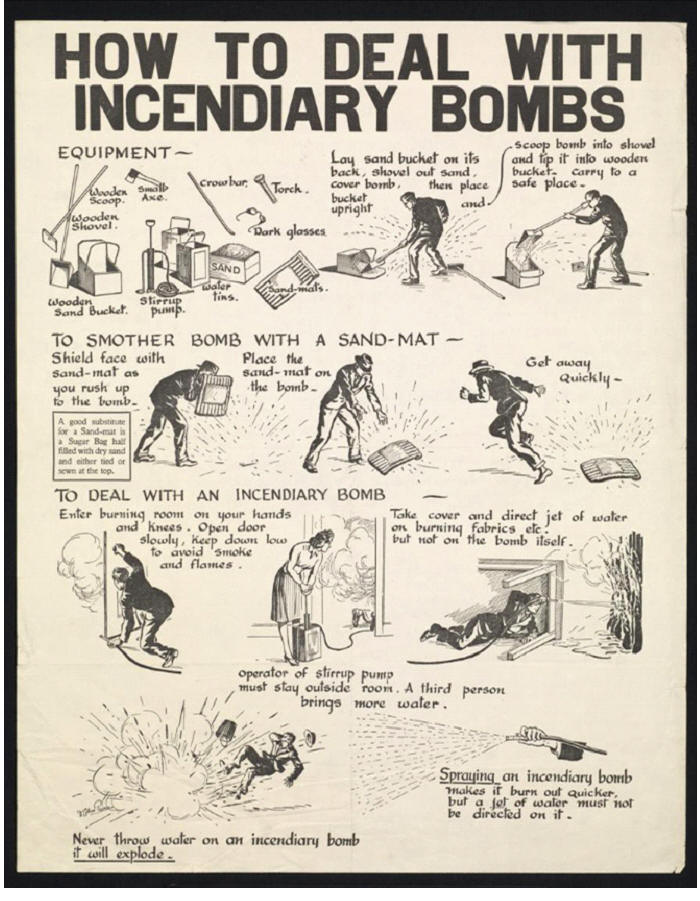

Anyone who was fit, able and not involved in other aspects of the war was expected to act as a fire watcher, often based in high buildings and vantage points or on the roof of larger buildings. Students, people waiting call up and anyone not gainfully involved in Civil Defence were encouraged to help and the job could be nerve wracking, standing completely exposed on a high building at night, often in bitterly cold weather in the middle of an air raid, with no protection except a tin hat – and nowhere to run.

Although teams of civilian fire watchers appeared relatively ineffective, they were absolutely vital to the defence of the city and were able to spot small fires and incendiary bombs in gutters and roof valleys that were hidden from street view. This was especially important in industrial and commercial sections of a city where buildings would be empty overnight. Teams would be on the roof watching neighbouring properties for trouble and if firebombs landed would attempt to extinguish them, or to direct the fire service to the incident before a fire took hold.

Frank Newbery who was involved in Starfish, until called on in 1942 to build ASDIC sets for the Navy, comments that one of the reasons why some towns were badly damaged by fire bombs and why decoys were often ineffective may be that residents often left the town centres for safer areas each night and as a result there were far fewer people to deal with incendiary bombs. This was also considered cowardly and selfish by those who stayed behind, but there was a far more serious problem and statistics also showed that the citizens who left the City to find lodgings in the countryside each night actually contributed to the damage.

Time was of the essence when a bomb landed and while most fell in gardens and streets, those that hit a building could usually be dealt with if tackled immediately, before a fire took hold and before it became visible to fire watchers - or from the air. Later in the war some firebombs were fitted with explosive charges to deter any approach, but where buildings in Bristol and other cities were occupied, they generally survived unless demolished by a direct hit from a high explosive bomb whereas unoccupied buildings, despite the fire watchers stationed on nearby rooftops, were usually well alight by the time the fire was tackled.

While a direct hit from an HE bomb had no defence, these were relatively few compared to the thousands of incendiaries that rained down and it was these that did the real damage. If the householder was still in residence, the noise of a small fire bomb landing on the roof and possibly breaking through into the accommodation would be heard and could be acted upon immediately, thus saving the property from total destruction. If left to burn, the bomb would do its worst unchecked. In these cases the main weapons against the Germans were buckets of sand, gloves, water and a stirrup pump. Incredibly basic but very effective ….. if there was someone there to act quickly.

However it did not need many unoccupied buildings to start a major conflagration that would stand out like a beacon to other bomb aimers and thus a relatively few people seeking safety outside the City could actively harm its defences, particularly if a decoy was in use.

Public information about fighting ‘Firebomb Fritz’ was promulgated for a very good reason.

c IWM

K: Decoy Airfield

. Daytime dummy airfield, storage depot or factory with buildings, fake roads and structures. These sometimes used inflatable or mock up planes, tanks etc and deceptive painting and groundwork to simulate a large military of industrial facility.Q: Decoy Airfield. Night-time use with dummy flare path lighting, obstruction lights and sometimes simulated aircraft landing lights or trolley mounted lighting effect of moving planes.

QL: Night Decoy. Simulating a badly blacked out town or factory complex. A typical detail was to provide a blacked out box with a half open door and a light inside. This was switched on and off automatically and appeared as if a door in a blacked out house of factory was being opened occasionally with light from inside apparently streaming out. Other decoys included skylights with ‘missing’ blackout paint and ‘windows’ showing chinks of light.

Minor SF – Special Fire (Minor StarFish): Night decoy of a small town or factory complex with fires and possibly lighting to simulate bomb blasts and burning buildings. Also used as a spoof navigation point to misdirect navigators. Could be used to simulate a successful attack on part of a large town.

SF - Special Fire (StarFish ) : Night decoy with full range of fire and lighting effects to simulate a major bombing raid on a town or city. These could be huge sites!

QF: Smaller spoof fires. Representing a single target like an isolated factory and often included lighting and other effects.

Oil QF fires.: Attempting to replicate burning oil storage tanks , however early designs were incredibly fuel hungry. Early trials burned up to 2500 gallons of oil per hour at a time when fuel was in very short supply. It was thus possible that in a long air raid with multiple decoys, the use of fuel could potentially have been higher than if the genuine storage tanks had been bombed. Experiments with alternatives indicated that a circular ring, crescents or pool fires looked just as good from the air and were much easier to build and operate - and used less fuel.

A standard oil decoy was a complicated arrangement with a six man crew and electric ignition. It consisted of :

The oil decoys were surrounded by a low earth bank to retain any leakage and the decoys at Downside were each fitted with small steel gate sluice in the bank. These consisted of a simple sliding 3mm plate with retaining channels set in concrete. The plate was connected to a wire so that the sluice could be raised and lowered from a distance. This was very basic, but the oil decoys were built rapidly and intended to be bombed and if necessary easily repaired. It is likely that the sluices were fitted so that when well alight they could be raised to let blazing oil pour through the opening to simulate a bund failure of an oil storage tank. It is known that this was done at a northern steelworks to simulate a total containment failure of a Bessemer converter and would have been a logical addition to the decoy. Any bombed and burning tank would be likely to leak blazing oil into the surrounding area, and the special effects crew were happy to oblige. (Bob Hunt – Portsdown Tunnels www.portsdown-tunnels.org.uk )

Remains of an oil decoy sluice at Downside 2

As Oil QF fires were intended to replicate burning oil depots, they needed to be located near to the real thing and local civilian oil companies were instructed to operate them because it was believed that they could provide the fuel and manpower more easily than the RAF. However there was a natural reluctance by oil depot staff to do anything to actively attract German bombers anywhere near a genuine target and thus most oil decoys remained ready for use but unfired. This was one of the very few failures of the decoy system and even Col Turner described the time and effort put into building these unused sites as a ‘calamity’.

It is known from local knowledge ( after the war Dave Ridley was told off as a child for getting plastered in black gunge from one of the pits ) that the oil decoys at Downside were still filled with partly burned oil, soot and filth and thus must have seen some service. As they were not near any oil depot, they were presumably operated by the RAF site crew but despite appearing on the 1946 aerial photograph, and being in situ in 2019, there is no record of any oil decoy at Downside.

Frank Newbery in March 2019 at the site he helped to build on Wrington Warren. Frank joined Colston Electrical Ltd as a 16 year old apprentice the day after the first Bristol Blitz.

He was immediately involved in constructing and operating the Downside StarFish before moving on to asdic and electronic counter measures later in the war.

A sight to warm the hearts of the StarFish planners, if they had seen it.

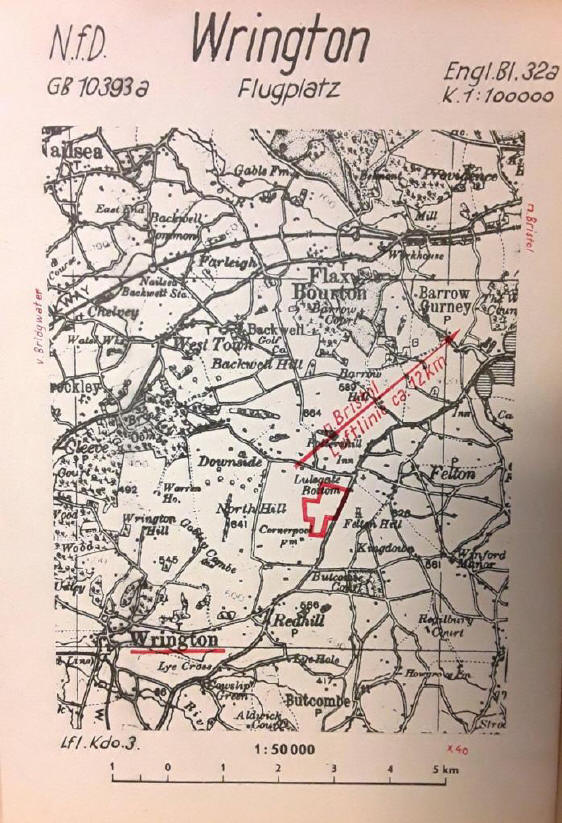

A Luftwaffe target map showing Lulsgate Bottom Airfield, but with no sign of the Downside Starfish. The Blackdown StarFish site was used by the Germans for navigation, but Downside was never discovered.

'

Report on Decoys' 23rd January 1941The Bristol and South West decoy fire sites were built by local firms William Cowlin & Sons doing the building work and basket construction, Haydons and the well known Bristol firm of Arthur Scull ( later Drake and Scull International plc ) doing the plumbing with Colston Electrics wiring it all up. These companies then went on to build many more sites all round the UK. ( Kenneth Comer – Somerset Archives )

Special Fire decoys (StarFish) were constructed as two types – major and minor. Downside was a minor StarFish, intended to replicate a particular area of a city or industrial complex that was under attack whereas the major StarFish was huge and could only be fired on command from the regional controller. Full sized sites required prodigious amounts of fuel and effort to fire and re-supply after use although lighting even a minor StarFish used over of 50 tons of coal, straw and wood plus huge quantities of diesel oil, all with two reserve sets ready to go if the raid was a long one. A long night for a minor site would still burn 150 tons of solid fuel with the potential to consume 100 gallons of diesel every hour ! Given the smaller size, later in the war the crews of minor decoys had discretion to fire if for some reason the local controller could not be contacted but larger ones required higher authority.

StarFish effects were generally split into four types of fire system.

Crib Fires – a large metal cage on legs containing brushwood, roofing felt, creosoted sawdust and any other locally available material that would burn well, usually topped with a thick layer of coal to extend the burn for several hours after the initial furious fire. They were usually ignited by flare cans under the crib to ensure a rapid burn.

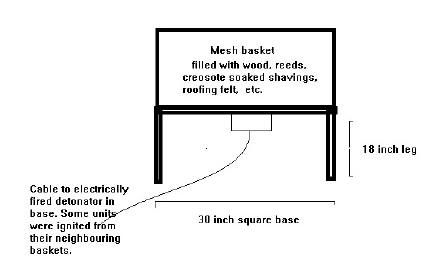

Basket Fires – similar to cribs but on a smaller scale and frequently grouped together to look like a row of houses, Ignited individually or placed near each other so that one lit the next to extend the burn time without operator intervention.

The cheapest and easiest to operate decoy – a ‘Bramerton Basket Fire’ filled with anything that would burn !

Brushwood, creosote soaked roofing felt and coal to provide a longer burn were favourites, but just about anything was used if it could be sourced locally and burned fiercely.

Grid Fires - diesel oil in a large tank on stilts fed into a sprinkler pipe up to 40 feet long creating a dirty yellow smoky flame to simulate a burning factory or supply depot.

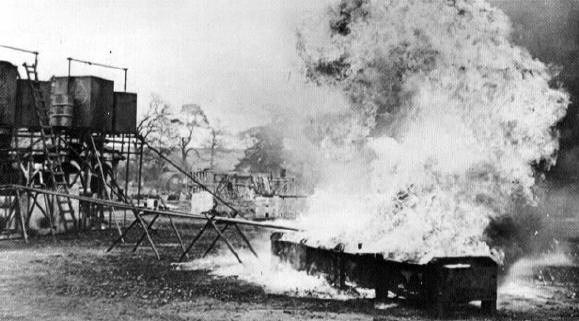

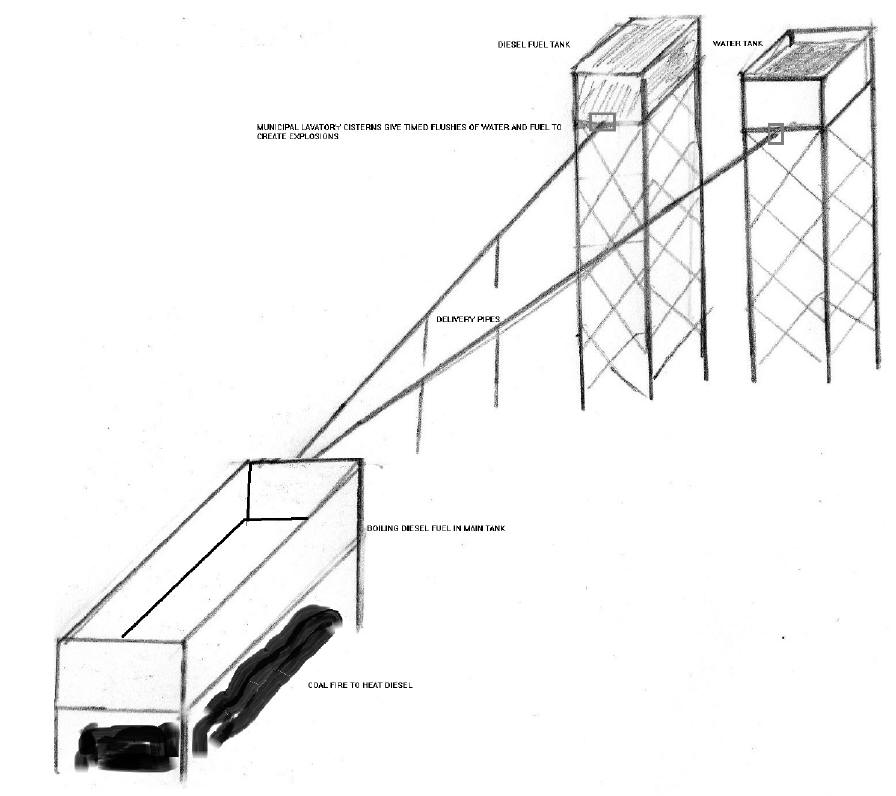

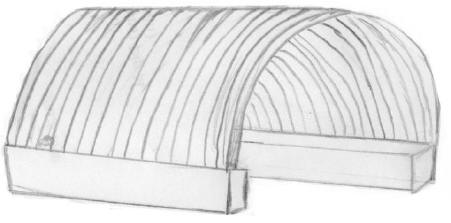

Boiling Oil Fires – these were the piece de resistance of Turner’s equipment. Large steel open troughs of standard design, 30 feet long, 18 inches deep and 30 inches wide. on short legs and filled with oily waste. Underneath there was around half a ton of coal , roofing felt, creosoted wood, brushwood and anything else available that would light quickly. Ignited electrically, the brushwood lit the coal and the inferno heated the tank above. Diesel oil was then fed into the tanks from 500 gallon fuel tanks on stilts where it boiled, vaporised and virtually exploded creating huge columns of flame and smoke. But Loudon’s designers had another trick. A second ‘fuel tank’ alongside the diesel one was filled with water and from time to time emptied some if its content onto the boiling inferno creating a violent explosion, smoke, sheets of flame and sparks. It was hoped that this gave the impression of a collapsing building. The effect was certainly awesome at ground level to the extent that firebreaks and trenches had to be built to contain the overspill of blazing liquid, despite all the decoys being built on waste ground and intended to be on the receiving end of tons of H.E. The water supply system was ingeniously based on municipal lavatory cistern with an automatic flush, providing regular and automatic deluges with quite dramatic results. This was an improvement on the original and unreliable system that required a length of cord to burn through to release the water.

Asbestos sheets were used to reflect light from the fires as if they were near remaining buildings and all this was controlled from a small bunker one thousand yards away by two very brave RAF men who operated the site and three others who at times had to venture out during an attack to repair damage caused by bombs!

Oil pool and horseshoe oil decoys – as described above. These were used at Downside but not generally on other StarFish sites. They were located to replicate oil storage tanks.

Other ‘specials’ -including rolls of roofing felt that were mounted above each other on a grid and the roll tied up with string. The lower one would be set alight and as the strings eventually burned through, the roll above would unwind and catch fire, thus perpetuating a ferocious blaze without the need for human intervention.

The sites needed to light very quickly and were set off when an air raid had started in the short interval between the initial fire raising bombers leaving and the main force arriving. Due to the limited endurance of their aircraft which were all medium bombers, the Germans did not have a ‘Master Bomber’ system where one aircraft crew would continuously observe the raid and direct the others by radio and thus navigators were often unaware that the target suddenly moved location after the initial strike or that the effects repeated themselves after a set time.

A boiling oil fire in action

A schematic diagram of a boiling oil fire decoy.

Fuel and water held in the large tanks were fed into municipal lavatory cisterns that flushed automatically, allowing an alternate charge of diesel oil or water to flow into the boiling and burning oil already in the main tank pre heated by a coal fire beneath. The result was fully automatic and regular spectacular bursts of flames and smoke followed by huge explosions as the water hit the boiling oil. These appeared from the air to be collapsing buildings and factory fires on a gigantic scale.

The system made a fearful mess and burned hundreds of gallons of fuel with each operation, but in the right conditions decoyed many bombs.

Illustration by Gill Floyd.

Although the equipment was installed by travelling teams, and had basic designs and methods of construction, the actual specifications were based on what was locally available. The Bramerton fire basket was a simple angle steel and mesh affair made by the company more famous for domestic stoves and appliances. It had a solid framework that was filled with combustible material and could be reused, but many of the local Bristol decoys were made from a canvas covered wood frame with a mesh outer that fitted onto a steel base. Made by the hundred by local building firm William Cowlin Ltd, production was based in an old barn on Stockwood Lane. After the baskets had been used, new ready made ready to go decoys were simply slotted on to the fixed base. ( Kenneth Comer – Somerset Archives ). The ‘Bristol built’ fire baskets were ignited with flash cans fired from the bunker’s electrical supply and others fitted with a basic timing device in the form of a 4 inch diameter, four foot long canvas oil soaked wick. This would self ignite from the first basket and in time would light the next one and so on to give the effect of an uncontrolled spreading conflagration.

Fire baskets alight.

Electrical ignition was used but this caused many issues with maintenance and even minor sites needed a team of 5 people and assistance from the local RAF stations. This took a lot of specialist manpower as the electrical firing systems were in exposed areas and open to water and animal damage – sheep and mice were a particular menace as they seemed to enjoy eating the electrical insulation off the control cables. The standard method of lighting was to use a firework cartridge with an electrical detonator made by Standard Fireworks. Filled with gunpowder these rapidly set fire to the main decoy but being cardboard were very susceptible to damp and wet connections, so maintenance was continuous.

Other methods of lighting were tried and some baskets were co located so that one fired the next. Having tried manual methods including hitting an incendiary bomb on the nose with a hammer, shoving it into a fire basket and running away, electrical operation from a distance that ignited flares inside the baskets and oil troughs was found best, and for some reason appeared far more popular with the men on site. Unfortunately some Air Ministry bureaucrats and serving officers, one of whom was Air Marshall Dowding, whose foresight and central control system effectively won the Battle of Britain, attempted throughout the war to return the system to manual lighting to save money and, they believed, man power. Thankfully Col. Turner managed to prevent this and the system remained very quick to start when an air raid was approaching as this was a vital part of the deception. It was just not possible for an entire site to be ignited manually without a huge team on permanent standby.

However there is an aside to the issue of ignition as Dowding was very aware of technology and would not have been against electrical ignition without a very good reason. Frank Newberry is perhaps the last surviving person who worked on the Bristol Starfish sites as an apprentice electrician, having joined Colston Electrical the day before the first Bristol Blitz raid on 2 November 1940. He recalls a demonstration that was arranged for the top brass of the Air Ministry before the site was moved to Brockley Wood. This was attended by some very senior people and as a major demonstration it is highly likely that Dowding was present as head of Anti Aircraft Command. The ignition systems for the baskets and fires were ignited by low voltage electricity controlled from a Post Office ‘uni-selector’ switching system that enabled the operator to easily select the decoy to be ignited. Although the setup needed regular maintenance it was generally reliable, but on this occasion there was a complete fiasco and the ignition system totally failed together with the water release for the boiling oil fires, leaving some very unimpressed Air Ministry officials. The site crew then had to rush round lighting the decoys manually and releasing the water. Frank recalls it was a spectacular display with tremendous explosions and huge flames. However the failure of the ignition system which was absolutely critical to the rapid lighting of a decoy while the bombers were approaching may well have led Dowding to believe that manual ignition was more reliable and less likely to fail, hence his strenuous attempts to introduce it and dispense with the electrical apparatus.

The decoy system was another example of an integrated air defence. The first task was to monitor and detect the German radio beams which were switched on and tested with Teutonic efficiency on the morning of the raid. This was done precisely to schedule every day and the RAF would be waiting with airborne radio detection planes to find the intersection point of the cross beams which gave the likely target. They would then prepare the local StarFish sites while setting up the lorry mounted and static radio jamming devices to ‘bend’ the radio beams and brief the local noisy but totally ineffective Anti Aircraft ( A. A. ) guns that did wonders for morale but almost nothing for air defence in the early years of the War. The radio countermeasures were absolutely top secret and vital that it remained so as detecting the beams and decoying the bombers were the only effective means of defence.

Frank Newbery remembers that at the start of the war, both the alert to prepare the relevant crews for possible action that night and later the ignition command would be sent by dispatch rider from the Whiteladies Road HQ and this involved a delay. A telephone was not used for the initial warning, possibly to maintain the secrecy of beam interception.

When the air raid began it was vital to enforce the blackout of all lights in the genuine target area and wait until the first wave of aircraft had gone home while frantic attempts were made to extinguish the early fires they had caused. When the observer Corps and Radar stations indicated that the first wave had gone and the main bomber force was approaching the command ‘FIRE STARFISH’ was sent to the operators of a main decoy such as Blackdown or in the case of a fire decoy like Downside, ‘FIRE MINOR STARFISH’. Initially the crews had to wait for authorisation and this degraded the effectiveness of the whole system.

In particular during the first Bristol raid on 2nd November 1940 , the one site that was ready and waiting to light at Whitchurch remained unused as no command was given to light. This caused fury amongst the site crew, Jack Dewer the contracts manager from Colston Electrical who had organised construction, and the others who had been involved in making the decoys. That night Bristol received 5,000

incendiary and 10,000 high explosive bombs which did a huge amount of damage. Frank later heard that a dispatch rider had been killed while on an ‘urgent journey’ during the raid and always wonders if this was the reason that Whitchurch was not used - the message never got through. It appears that for later raids the ignition command was given by telephone although the daytime alert still came by dispatch rider as presumably the advanced knowledge had to be kept secret from prying ears and the decision to light was self evident given the rain of explosives.The first sites were experimental, rushed and built from whatever was available and sited wherever possible. In the case of Downside 1, the original bunker was a single thickness breeze block construction and about 100 yards from the edge of the decoy site. This was incredibly dangerous as it was not only well within the margin of error of accurate bombing but also in the blast range of larger munitions! After the initial rush to build decoys, later sites had rather more preparation and planning and the substantial control bunker was located about half a mile from the site although a wayward bomb could still hit it as nearly happened at Downside. Designed for an incredibly hard life, later decoys were professionally built and wired up by dedicated teams and then maintained and operated by detachments of 5 RAF personnel with a travelling squad of technicians to perform major repairs.

Refuelling the decoy sites was a long and messy business as the fire decoys were soon sooty, oily, muddy and blackened. They required tons of material, hundreds of gallons of fuel and if successful, were full of holes and craters with delayed action and unexploded ordnance for good measure. The local RAF station was usually called to send a re-supply team and as it was not know when the next raid might come, the job had to be done urgently, regardless of weather conditions. Repairs had to be made as damage was frequent, wiring needed to be checked and new fuzes and igniters installed. Much of the wiring would be damaged or burned out when the site was fired regardless of bomb damage and it was a long job to get everything back to readiness. As the fire baskets were often filled with creosote soaked material they were usually refilled by the junior members of the site crew and Frank Newbery recalls having burns and blisters caused by the creosote on his skin.

Where possible a site was constructed in two sections so that there was always another firing available if there was a raid the following night before the first site had been refuelled. Special Fires were supposed to have two complete reserves of fuel, but in the event of a long raid this could be used up and the job of replenishing was filthy and back breaking. At times hundreds of gallons of fuel and 150 tons of flammable material had to be delivered, unloaded, moved round the site and set up as a matter of extreme urgency on what had literally become a slippery and oily bombsite in the middle of nowhere with rubble covered farm tracks for access.

One issue that was unforeseen but very real was the problem of thunder storms. The electrical firing system was of low voltage and a strike nearby, made more likely by the open nature of most sites, could induce a current in the ignition system and spontaneously set off the entire site, and the reserve. This seems to have happened on several occasions and Frank Newbery was thus detailed to install a lightning conductor at Downside. Having been on site and seen several strikes, he was aware that the large amount of iron in the ground caused the discharge to ark and travel at ground level and that a conductor would be useless. While he was building the site he warned a visiting RAF officer about his concerns and as a result the lightning conductor was abandoned and all the decoys at Downside were fitted with a simple isolator switch to prevent induced current ignition – of course as the junior, it was Frank’s job to fit them all into place.

A consequence of a successful decoy operation was the huge amount of ordnance deposited on the site in addition to the damage done to the equipment. With craters deep enough to swallow a car and hundreds of incendiary bombs lying around and HE ordnance on time delay fuzes or with anti handling devices, clearing up was a big job.

Frank Newbery describes the bomb disposal men as ‘complete lunatics’. They were incredibly skilled and very professional but seemed to have a somewhat irreverent approach to the most dangerous weapons yet built. He recalls being sent to refuel the Chew Magna site after a firing and seeing the area littered with incendiary bombs, many sticking out of the grass and unexploded, together with many small red flags on sticks that indicated a buried ‘UXB’. Having watched as the disposal teams dug out and defused bombs while he was refuelling and repairing the site, he returned next day to find the areas where he had been working were now transformed into huge craters from the bombs that had not gone off immediately but on a time delay. The disposal men lived with this risk and accepted it as their part in protecting the Nation. Frank also remembers that after the first firing at Downside there were hundreds if not thousands of incendiaries scattered about the fields. These were collected and burned on orders from above although this seemed to be a dreadful waste of magnesium which was in great demand for the war effort. However after a violent explosion from the pyre it was realised that some incendiary bombs had a small anti handling charge under the tail fins and that this made the risk of reclaiming the material too high, so the order was given to incinerate the lot.

To show how dangerous it was to put yourself in the firing line at a StarFish site, the Bleadon decoy was the scene of a Military Medal award on 4th January 1941. Aircraftsman 2nd Class Cecil Bright, the lowest rank in the Air Force, was on station when the order came to light the StarFish. The ignition system failed, probably due to the damp marshy conditions and close proximity to the sea, and with a raid developing on Weston Super Mare, he made the decision to ignite the decoys manually, spending the next 3 hours crawling about the site lighting the decoys with matches and a milk bottle full of petrol. The decoy fires took hold rapidly and before he could get back to the control bunker, the raiders transferred their full attention to the StarFish, leaving Bright exposed to the hail of munitions in an open field. He returned having made his way along several ditches, filthy but unscathed. The next day his colleagues recorded 42 high explosive craters and 1500 incendiary bomb fins on the site . The citation for his medal stated "Due to reasons of National Security, details of the act for this award can not be disclosed" and it never officially was, but the King knew and he received his medal at Buckingham Palace on April 5th 1941. Weston was badly hit but the majority of the raid was diverted because of his bravery – and the StarFish.

All this may seem incredibly Heath Robinson, but resources were limited and decoy sites appeared quite convincing on cloudy or misty nights and were effective in more ways than just attracting bombs. There was just no other effective defence and the importance of the scheme was reflected by Turner’s carte blanche to call on any materials or assistance to set up his decoys and the above top secret classification.

There was another very significant benefit of the decoy system that was unquantifiable but highly significant, that of creating confusion and distrust of navigation aids amongst the poorly trained German aircrew. In the early days the Germans had no advanced directional aids other than in the lead aircraft which were fitted with apparatus known as ‘ X system’ and the later highly accurate twin radio beam ‘Crooked Leg’. As previously described, the leaders acted as pathfinders for the main force who were briefed to look for the flares and markers dropped and fires started by the lead planes. A number of main force bombers became lost over the UK as a result of the chaos created by targets that suddenly seemed to move or were apparently in the ‘wrong place’. Planes that had been flying for long periods trying to find their position ran out of fuel or crashed trying to land at their base, flew into hills or went wildly off course. Problems of night navigation were exacerbated even for the expert navigators in the pathfinders as their electronic and traditional aids and maps gave one position and looking out of the window showed something totally different or even worse for a seasoned aviator, slightly different. This caused a serious loss of morale amongst crews who began to mistrust their electronic equipment and even their colleague who was navigating! This was not always the case, and on clear nights things usually went well, but it chipped away at confidence, accuracy and even destroyed some aircraft that were otherwise impervious to the near useless ground defences.

Later in the war, the delays in position checking prior to bombing clustered Nazi planes into a smaller area and made them easier prey for British night fighters but in late 1940 there was no effective British night fighter radar and while it would soon come into service, our night fighters could be only directed towards the enemy using ground radar control. The critical final mile of interception needed moonlight …. and good luck. A few night fighters had prototype airborne interception (A.I.) radar and although horribly unreliable at first, it did begin to have some success and was behind the legend that carrots aided night vision. To provide a cover story for airborne interception it was claimed that the successful fighter pilots had excellent night vision and ate carrots to improve it !

Dave Ridley indicating the site of a decoy oil fire on Wrington Warren.

Despite his requests to preserve the heritage of the site, all the equipment was carted away for scrap leaving almost no sign it had ever existed.

A row of possible bomb craters in Chelvey Wood – almost 80 years after they were formed.

Many other depressions appear like craters but are actually the results of mining and quarrying for the local stone walls.

T

he first of the 'Q' or decoy ‘ Special Fire’ sites were in place, after a fashion, around Bristol by late November 1940. Initial sites at Whitchurch/Stockwood and Chew Magna were followed soon afterwards by further installations all round the city. Bristol was the first to have these and once the procedure was established they were installed at a rate of about one per day around the UK until June 1941. While there were a number of teams working on the project, the speed of construction indicates the basic nature of the installations which were designed to visually represent a particular aspect of local infrastructure with materials often adapted from what was available locally. As the sites succeed by self destruction there was little point in fine detail although the later control bunkers have withstood the test of time and many remain in good condition.Major decoy sites for Bristol were at Sheepway ( Portishead ), Severn Beach, Lawrence Weston, Patchway, and Yeomouth ( Woodspring Bay ) but surprisingly the one at Downside is largely undocumented.

Downside seems to have received the attentions of the Luftwaffe on at least three occasions while Bristol decoys received a total of ten attacks. There was also a dummy lighting ‘QL’ site on Kenn Moor where the control bunker can still be seen near the model aircraft club. This is not believed to have had an attack.

The main decoy site for Bristol was a huge edifice on the Blackdown Hills at Tynings Farm, above Burrington Combe. South of the City it was laid out over many acres to represent Bristol Temple Meads railway station and marshalling yards with complex lighting and all currently available fire effects installed. It was truly enormous but was never actually used in anger and never received a bomb. The author has seen a German navigational document that highlights Blackdown as a good navigation marker and thus it is unlikely to have fooled anyone. This shows how important it was for decoys to remain top secret and only operated in the right conditions as in this case all the effort put in to create Blackdown merely assisted the enemy’s navigation. The control bunker is now a historic monument and can be visited.

http://learning.mendiphillsaonb.org.uk/starfish-black-down

A main cause of the destruction of Bristol – an HE111 bomber

Civil Bombing Decoy SF1 (c)- Downside

[Ref.: AIR 19/499]

S.67000/FC.34

SECRET

‘STARFISH OPERATION INSTRUCTIONS TO LOCAL CONTROLLERS’

"MINOR" STARFISH

In view of the present enemy tactics [scattered bombing with target indicator flares] it has been decided to provide a small fire consisting of one group of baskets on the undermentioned site(s) which you control, and this fire will be known as the "MINOR" Starfish.

2. The "MINOR" Starfish will be under the control of 80 Wing and

the intention is that they will operate it:

(i) when the line of approach of

enemy aircraft is known;

(ii) when a concentration of enemy

aircraft show signs of being broken up or dispersed.

3. In this connection, it is most important that the sites should have received a standby warning immediately you receive a "Purple", or any indication that enemy aircraft are approaching the Area.

4. Attached is a copy of the instructions to operators on the sites, and it is requested that you will pass any information of enemy activity received from the site to 80 Wing with the least possible delay.

5. If 80 Wing order a "MINOR" Starfish on the site the instruction should be passed on in plain language, i.e. Fire MINOR Starfish".

6. Contact should then be maintained with the site and with 80 Wing. If the site should report an enemy attack on the MINOR, 80 Wing would wish to know about this, and they would then indicate whether the fire was to be extended.

7. In the event of a breakdown of telephone communications between your Headquarters and Starfish Control at 80 Wing, you are authorised to fire the MINOR Starfish, and if the site is attacked, to extend the fire as necessary. Having taken this action, every effort should be made to inform 80 Wing as soon as contact can be re-established.

21st March 1944

E.M.Selby,

S.F.

for Wing Commander, Section 2 (Operations)

Col. Turner’s Department.

[Ref.: AIR 2/4760]

D

ownside was commissioned in late 1940 at a site adjacent to the airfield where ‘Tall Pines’ Golf Club is now located. Known as SF 1 (c) it was under the control of 927 Squadron (County of Gloucester) Balloon Squadron AAF. Overall site administration for the Bristol decoy system still came from the military base in Whiteladies Road, Clifton, Bristol, opposite the BBC site and now the Territorial Army Centre.At the time the project began, Downside was an open heath, rich in wildlife with countless rabbits, from where Wrington Warren got its name, and plovers nesting amongst the bracken. The plovers were a very noticeable part of the wildlife and are remembered by all who knew the heath before the StarFish arrived.

Initially the site was built to the West of Cooks Bridle Path, a road that now runs around the back of Bristol Airport. A control bunker was constructed near the road and the decoys were laid out on the open ground beyond it. Part of the first control bunker wall can still be seen next to the golf club maintenance compound and the decoys were set up on the plateau and valley to the west of where the golf club house now stands. At this time the decoys were fire baskets and boiling oil fires using the oil and water tank system with heated oil troughs. The six airmen who operated the site were billeted at Combe Head Farm nearby.

The original site was extremely close to what would become the airfield runway when RAF Broadfield Down, later renamed RAF Lulsgate Bottom, became a training establishment and emergency landing ground. Having a decoy target less than half a mile from an operating RAF station was considered counter productive, even by the bureaucrats at the War Office and in 1941 the StarFish decoy was relocated to Brockley Woods about a mile to the west.

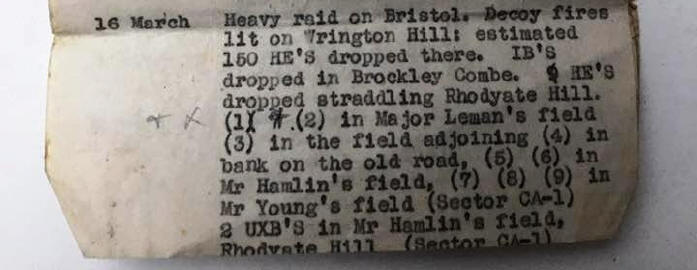

The date of the move is unrecorded but Frank Newbery recalls laying out the new site early in 1941 and a cryptic note from an air raid warden’s report of the raid on 16th March notes that ‘decoys were fired on Wrington Hill’. This seems to indicate that even if the new site was under development, it was partly operational. It may be that for a time both sites were used as the raid to which this note refers had widely scattered bombing at first with both the original and the new site locations receiving multiple hits. It is unlikely that the Germans would have been several miles off from a clearly lit target and it may be that there were two in operation as bombs fell around Cleeve and in Brockley Combe. Given the speed at which decoy sites were constructed, it is quite possible that at least part of the site was ready to use at this time. The early scattered bombing on this raid may demonstrate confusion amongst the German bomb aimers although accuracy improved alarmingly later in the night and Bristol suffered heavily. The move from Downside 1 at Tall Pines to Downside 2 at Wrington Warren was certainly completed by the Autumn of 1941.

In 1942 a ‘QL’ site was added to simulate a railway marshalling yard, using electrical lighting effects including red flickering bulbs to mimic a railway engine’s coal fire being stoked although there is also mention of a ‘dummy airfield’ approximately one mile south of the real thing with lines of lights and cables strung out to replicate the airfield lights. ( Kenneth Comer – Somerset Archives ). This is mentioned in a document held by Somerset Archives and was noted by an eyewitness although not referred to elsewhere, but neither is the ‘marshalling yard, and both may be referring to the Mendip Hills major StarFish complex at Blackdown/Tynings Farm.

The Downside site seems to have very few records and what can be found is from personal memories and the RAF survey photographs taken in December 1946 of Downside ‘2’ when the entire country was survey prior to the demobilisation of many RAF reconnaissance squadrons. While the first site was somewhat experimental the second seems to have been built with experience from the previous decoys and was one of the later ones constructed. It was accessed from Brockley Combe and laid out on heath land known as Wrington Warren

Once the final location of ‘Downside 2’ had been decided, a combined control bunker and generator room was built to the south on raised ground near Warren House about half a mile from the decoy fires but connected by the main access track over the Warren. The various ‘Special Fires’ were positioned on the heath land ( now woods ) to the West. By 1946 most of the decoy sites had been erased by the RAF as a matter of national security and only a few twisted remains and blackened ground remained to indicate anything had existed. Hence an accurate description is almost impossible, but as far as I can ascertain the site was set up at the eastern end of the Warren about half a mile from the access road that went to the few houses in the area. The access to the site was known as ‘the cinder track’ branched off the main access and after crossing a small belt of trees crossed the open heath of the Warren, It was constructed by the RAF construction team from rubble, stone and plenty of cinders and thus got its name. The track ended in a turning circle about 100 yards onto the heath close to what is now the western side of the Fountain Forestry depot with a smaller track curving to the north west to service the more remote fire decoys.

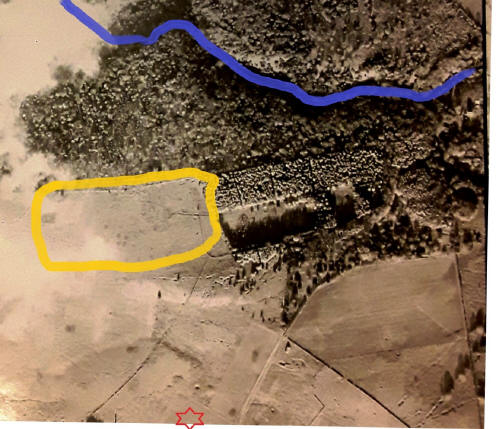

Beyond the turning area to the West, StarFish decoys, mostly baskets and boiling oil tanks were constructed. Fire baskets of the wooden type were also used (Kenneth Comer – Somerset Archives) and a stone hut with concrete foundations was built on the northern side of the Warren against the boundary wall and still there in the early 21st Century (Dave Ridley). On the photograph there is clear evidence of oblong marks on the ground that appear to have been grid fires or possibly boiling oil troughs laid out in a precise pattern to the south west of the turning area although frustratingly the western part of the site is covered by the only cloud in the area on the day the photograph was taken, and the ground is obscured from view.

At some point a large oil decoy was added to the site and this was created to the West of the turning area about 100 yards further into the woods, with four oil decoys grouped together and others on their own a little further away. There seem to be seven remaining as at 2019 but previous forestry activity may have destroyed some as they

were merely a low circular earth wall with an outlet on one side. The decoys were intended to replicate gasometers or oil tanks. These were fuelled by oil and equipped with a small sluice gate in the outlet that could be raised to give the impression of a leaking and burning oil tank. Dave Ridley remembers getting into trouble as a child by playing in the circular enclosures after the war as they were filled with crusty black oil and filth. The Author and Dave Ridley surveyed the remaining seven circular fire pits still in place in 2019 and these can be seen on the 1946 RAF photograph although the other equipment is long gone. Some sluices are in place but most are rusted away. ( Author & Dave Ridley - November 2018 ). The main site was laid out in two sections, each having six clusters of four fire baskets and the associated oil tanks and fire troughs. One could be ignited and the other held in reserve.

This part of the site was reasonably compact but there seem to be some additional less used decoys in another cluster about 150 yards to the west. On the western side of the Warren are some large circular marks that seem too big to be bomb craters and also a few scattered craters. Looking at the overhead photographs, it seems possible that there may be more oil pits to the West including a possible horseshoe decoy in Chelvey wood although I am advised that there were no additional units away from the main area. Thus these marks are unidentified.

The new site was well located with good access, secure and surrounded by woodland, the only unofficial access being a long trek up the steep hillside, thus it was hidden from bad eyes. As StarFish were beyond top secret, Brockley Woods must have been an ideal location, well away from habitation, isolated and well screened, yet with easy access by road and close to the airfield for technical support and fuel.

Circular oil fire pit at

ST 47783 65726 in the Downside StarFish

Remains of a sluice valve in the oil pit above.

While the second site was apparently used several times and clearly drew bombs, in truth the major German bombing campaign was over by the time it was commissioned and it saw relatively little activity. A great deal of work and effort was spent for a relatively small effect whereas the first decoy site, put together rapidly and on a shoestring, had superb results. The new site was built too late to play any major part in the defence of Bristol and by the time it was ready, the Germans were occupied with the Eastern Front and defending their own Cities from Bomber Command.

There are some large craters in the woods nearby but the site is now a commercially planted woodland and much of the evidence has been destroyed. There is no sign of bombing at the original location as it hosts the manicured lawns of a top rate golf club.

Downside 2 was shut down on 18th April 1943.

Downside 2 photographed in 1946 by the RAF ( Crown Copyright ).

The access ‘cinder track’ is visible together with the locations of the fires, grids and racks. The dark circles are oil fire pools.

The blue line is the route of Brockley Combe Road and the yellow line indicates the approximate extent of the StarFish. The Red star is the approximate position of the control bunker, just out of the frame.

The blue line is the route of Brockley Combe Road and the red line indicates the approximate extent of Downside 2.

It may have extended to the West as far as the broken red line but this is still being researched.

About a half mile south of the target area and well camouflaged is the control bunker , (arrowed red ) with what appear to be bomb craters ( yellow ) randomly disbursed to the West of Warren House.

The enormous bomb crater in the square shaped wood is clearly visible!

Dave Ridley indicating the enormous crater. The bomb came unpleasantly close to the control bunker .... and Warren House.

Two of these landed in the southern part of the wood, a very long way from the decoy fires. Now filled with rubble and brash, the outline can just be seen.

The control bunker for Downside 2 appears to be in very good condition and is located adjacent to Warren Cottage at the south eastern corner of the site. The blast wall seems to have been removed but the emergency exit is still visible and appears to be intact.

It was intended to be a long way from the action and connected to the decoy site by a trunk of cables, all controlled from a telephone selector switch that enabled the operators to set off various decoys as necessary. The bunker came alarmingly close to demolition as two huge bombs landed nearby in the adjacent copse blowing gigantic craters in the soil. If these had been nearer the location, both the bunker and Warren Cottage would have been demolished.

The Downside2 Control bunker on Wrington Warren. Only part of one wall remains of the first bunker on the site of Tall Pines Golf Course.

Please note – this is on private property and MUST NOT be approached without permission.

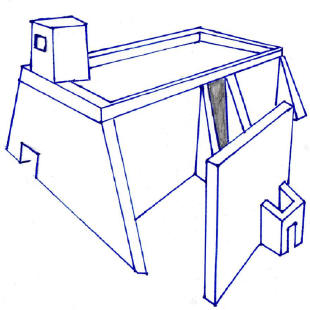

Under the earth mound – the design of a later type of control bunker similar to the one at Downside (which has lost its front blast wall. ).

Illustration by Gill Floyd.

There seems to have been no uniform design and once built they were covered in earth as additional protection. The turret structure was a lookout fitted to some and on QL lighting sites there could be provision for a brave man with a handheld searchlight to wave at aircraft passing overhead – suicidal !

The small enclosure on the blast wall is the coke store for heating. These bunkers usually held a Coventry Climax generating set with some sizeable circular ventilation holes at ground level for exhaust and ventilation these are to the rear and not shown.

Proof against splinters and some blast, the bunker could not have taken a direct hit and most were situated half a mile from the target zone although at Downside 1, the bunker was less than 100 yards away !

Another type of control bunker and generator house of StarFish sites – usually covered in earth for blast protection and situated about half a mile from the target fires or lighting sets.

This is the QL lighting decoy site bunker on Kenn Moor near Clevedon, on the the flood plain below the Downside site.

A

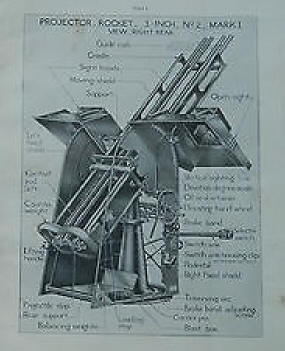

s I was finishing this text, a chance conversation with Dave Ridley, who knows the area from a lifetime of family involvement, brought up the subject of ‘Z Rocket’ projectors. He mentioned that shortly after the war he had seen a concrete plinth on the Warren that had brass numbers fixed to it indicating the degrees of the compass. Adjacent to it was a small hut with an open front that he thought had been used to house shells for some type of gun or launcher. This is an almost certain sign that a Z rocket system was installed near to the StarFish control bunker on Wrington Warren and eyewitnesses have reported the noise of anti aircraft guns on the site. As we know there were no guns, but the rockets sounded similar.

The Downside rocket site - remains of Z rocket ammunition store ( top ) and the lower illustration of what it was like when built .

Illustration by Gill Floyd.

A visit to the site indicated that three sets of low block walls still exist adjacent to the footpath together with some rusting corrugated circular steel that probably made up the shed roof.. These appear to have been the base of a small steel shelter that formed a store for the projectiles and there were at least three z rocket launchers at Downside 2. Unfortunately a track has been constructed through the site and trees planted commercially, so any others may have been obliterated.

A further set of parallel walls, this time at the QL site on Yeo Moor. However to add to the mystery, there is no recorded use of a Z Battery here.

Z rockets were a form of unguided missile designed to create a one time box barrage, akin to a gigantic shotgun. Manned by the local Home Guard, the weapons were aimed remotely and the operators on site had to set the elevation and direction and then ‘press the button’ on command from HQ. They were often installed near decoy sites and it is not surprising that Downside had some, although there is no documentation. There were high and low level batteries for dive bombing and high altitude attackers, but like most of the early wartime air defences, they had a very limited success. Over 50 emplacements were built in the UK during the war and a major issue seems to have been to keep the operators safe from the very powerful exhaust blast when the multiple launcher fired its 2" or larger 3" projectiles in one mighty blast as a ripple effect - over 100 projectiles in a full installation. At the pre set height the entire salvo exploded in one terrific blast creating a wall of flying steel fragments that was intended to obliterate anything that was inside the 'box'. Highly spectacular, the results were not good but it certainly kept the raiders at a high altitude and created a fearsome spectacle.

Various outbuildings were located out of the immediate blast zone for storing the ammunition and fusing the warheads and the remains of the concrete walls would confirm this. The rockets were six feet long and two were mounted on each emplacement although there are reports of over 50 units in some batteries and photographs show mobile launchers with around ten projectiles in one mounting. They had a delay action fuse so that the things detonated at the desired height, reported to be up to 19,000 feet. The wire carrying ones had small parachutes at each end of the cable and a small explosive charge, the idea being to snag an aircraft so that the drag of the ‘chute would then pull the explosive into contact with the airframe. Others just sent out shards of steel in the hope of hitting something. A major problem with this design was that while 500 feet of wire attached to small bombs sounded effective, what went up also came down. Miles of almost invisible wire and associated bomblets draped over trees and roads, railways and worse, power lines and empty rocket casings raining down caused havoc and probably did far more to hamper the war effort than a few misplaced bombs. The idea of filling a square mile of sky with shrapnel, wire and explosives sounded too good to be true and it was – there are reports of just two planes being brought down by anti aircraft rockets - and one of those was by an armed trawler on coastal patrol using a different adaptation.

It is not known how many projectors were installed at Downside or if they were ever fired, although there are rumours of an ‘anti aircraft gun’ in the vicinity. As there were none this may be an oblique reference to the rocket system as it was reported to be awesome, if ineffective.

Z rocket launchers – illustrations from the Internet

Frank Newbery recalls a conversation with his boss, Colston Electrical’s Contracts Manager and the ‘main man’ as follows:

" Thinking back to a discussion with Jock Dewer , the general idea with putting some rockets on decoys was for the decoy staff being able to fire them with any aircraft around to convince them it was an important site that was on fire so they would probably drop their bombs on it. The rocket battery would have plotted the flight of the aircraft and fired to hit it, so the rockets would have needed to be set up with some precision."

Thus again there were multiple aspects to decoy operations, in this case decoying the decoy.

There is an interesting page on the BBC website dealing with a London Z rocket site that is well worth reading. While not concerned with Downside, it has a degree of relevance and is the only available description I have been able to find about the operation of Z rockets.

Original document at : HERE

Bunker ST 47810 65475

Z rocket base ST 47758 65523

Z rocket base ST 47822 65492

Z rocket base ST 47825 65467

All these are on private land and are not accessible without permission from the land owners. Dogs run free on much of the site!

T